There are lots of pre-baked applications that let you set up Docker quickly, but many of them involve click-ops and don’t allow you to save your infrastructure as repeatable code.

This tutorial will show you how to get an EC2 instance (or many) up and running with Docker installed in a repeatable, and stateful way.

In order to get the most out of this tutorial, you should have a basic understanding of Terraform and some of the AWS resources that we’re creating, which relate mostly to networking and the VPC. Maximilian Schwarzmuller does an amazing job explaining those different components.

The complete source files for this tutorial are online here.

What are we building?

We’ll create a number of components:

- The VPC (virtual private cloud) that holds our subnet

- The subnet within the VPC that holds our EC2 instance

- The Route Table that configures routing for the subnet

- The Internet Gateway to make our resources available to the internet at specific IP addresses

- The EC2 instance, with Docker installed

- Security Groups (like a firewall) to manage access to the EC2 instance

This may seem like a lot of configuration for a simple Docker container! However, when using Terraform it’s best practice to create all your infrastructure from scratch so that when you cleanup, or run terrafom destroy, all of your resources will be deleted, including your VPC.

This architecture will allow us to easily deploy more containers in the future if we choose, and easily tear down our application.

Configuring the AWS provider

Within your project directory (I’m partial to creating a separate infrastructure folder for my Terraform files) create a main.tf file. This file will contain our AWS provider.

Think of the provider as the software that communicates with an outside party, in this case, the AWS API. There are a few ways of passing environment variables into Terraform for AWS, but I’ve found the simplest is to just load a configuration file into your AWS provider.

To do this, you’ll need to save your AWS user’s credentials to your local computer. Your configuration might look something like this:

[terraform]

aws_access_key_id=KLUHSUIDFB8972D989FSD92

aws_secret_access_key=fj9f&SDKsdfbsdlahsdf

[another-user]

aws_access_key_id=IUSI9UHFK971BA19

aws_secret_access_key=ksdfjn9sf91nfuwofYou can then load those credentials into your provider:

provider "aws" {

region = "us-east-1"

shared_credentials_file = "~/.aws/credentials"

profile = "terraform"

}The “profile” will tell Terraform which user to use when communicating with AWS. Make sure the user has programatic access to AWS!

Setting up our Variables

There are certain parts of this configuration that can be easily pulled into variables, like the SSH keys and the size of the EC2 instance. This will let us modify them in the future if needed. Let’s do that now.

Create a file to declare all of your variables.

variable "availability_zone" {

description = "Availability zone of resources"

type = string

}

variable "instance_ami" {

description = "ID of the AMI used"

type = string

}

variable "instance_type" {

description = "Type of the instance"

type = string

}

variable "ssh_public_key" {

description = "Public SSH key for logging into EC2 instance"

type = string

}Then create a separate file (which you will not commit to source code) that contains your values for each of these variables. This file is called terraform.tfvars and Terraform will pick it up automatically and initialize the variables inside of it.

availability_zone = "us-east-1a"

instance_ami = "ami-09e67e426f25ce0d7"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

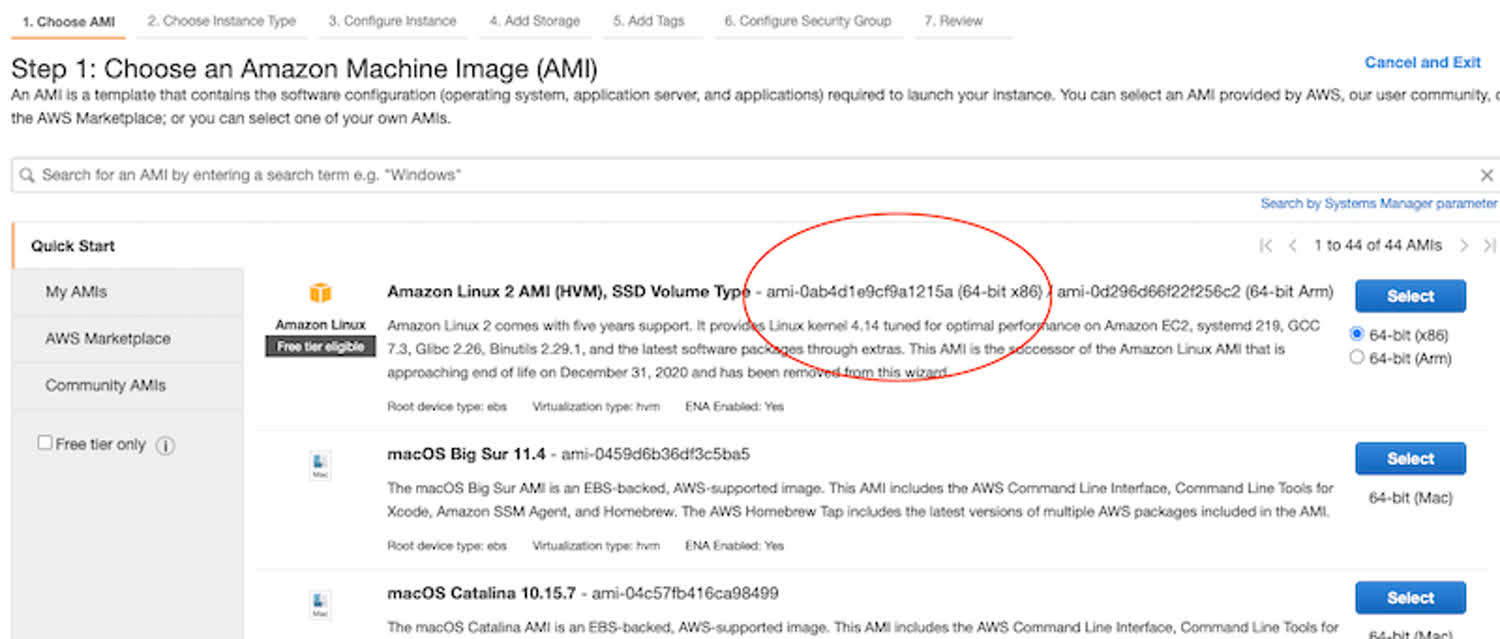

ssh_public_key = "ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQDQy/pHHnlxKiTFRH/FAbAgtLA2GBS45bTNxrrSP+tqtF0TSe1j/NSKD3+C7GPmVNTOU2SDL3UIu71EfNcDtjRZ9O7AhJvNczOHRQ/gK7Pi88tkVjs5jHImJK3Fx/GgJ1jXCSfR5eD9CAhGBeYS21aq9SCOPDEzY3Pie0pP/KODnCILcdlbX9vVHf/LXXzY41dWEfobuAOjiJ03YjPhPCNCpl2axO0kLPOvkXTkiA8vrn2CpHW/0sy+a2WwaHEJrJ2QARdhrTIi6w8dQWK8AE5xp/vuiTTHCInY04e19m9CZwRi/TbUsyttVaw4DgG9mozxvu7CeC0FLJWE1JGHLBn/ harrisoncramer@myPc.local"The instance_ami for the specific EC2 server you’d like to use by logging onto AWS, and launching a new EC2 instance.

This is where you can find the AMI of the server that you’d like to deploy.

When we setup ssh for our EC2 server later, the ssh_public_key will match with the private key from our computer.

Creating the Network

Our EC2 servers will need to live inside of a network. In AWS parlance, this is the VPC, or virtual private cloud. Let’s create it:

resource "aws_vpc" "main" {

cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/16"

enable_dns_hostnames = true

enable_dns_support = true

tags = {

Name = "EC2 + Docker VPC"

}

}The full list of options for the VPC is here. We’ll enable enable domain name support (perhaps we want to have a domain in the future). We’re also telling our VPC to have a CIDR block with suppport for 65,534 hosts, ranging between the IP addresses of 10.0.0.1 to 10.0.255.254. To learn more about subnetting and CIDR blocks, check out this introduction video on the topic.

Next, create our Elastic IP resource. The IP address is a static address that will not change, and we can map to our EC2 instance. In the future, if the EC2 instance goes down or is re-created, the public-facing URL will remain accessible at the same place.

resource "aws_vpc" "main" {

cidr_block = "10.0.0.0/16"

enable_dns_hostnames = true

enable_dns_support = true

tags = {

Name = "my_app's VPC"

}

}

resource "aws_eip" "my_app" {

instance = aws_instance.my_app.id

vpc = true

}You’ll notice that we’re referencing the aws_instance which is our EC2 server. We’ll create the actual EC2 instance resource in the next section. Terraform is smart enough to create our resources in the correct order, which lets us split our code across multiple files and not have to worry about runtime order.

Next, we’ll create a subnet within the range that we defined for our VPC. The cidrsubnet function calculates a subnet address within the given VPC’s CIDR block:

resource "aws_subnet" "my_app" {

cidr_block = cidrsubnet(aws_vpc.main.cidr_block, 3, 1)

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

availability_zone = var.availability_zone

}Let’s also create the route table. This will allow traffic from our internet gateway (which we haven’t created yet) to reach our VPC.

resource "aws_subnet" "my_app" {

cidr_block = cidrsubnet(aws_vpc.main.cidr_block, 3, 1)

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

availability_zone = var.availability_zone

}

resource "aws_route_table" "my_app" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

route {

cidr_block = "0.0.0.0/0"

gateway_id = aws_internet_gateway.my_app.id # This will be created when we apply our configuration.

}

tags = {

Name = "my_app"

}

}We also need to associate this route table with our subnet. Strangely, this is actually a different resource in AWS than the subnet and the route table:

resource "aws_subnet" "my_app" {

cidr_block = cidrsubnet(aws_vpc.main.cidr_block, 3, 1)

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

availability_zone = var.availability_zone

}

resource "aws_route_table" "my_app" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

route {

cidr_block = "0.0.0.0/0"

gateway_id = aws_internet_gateway.my_app.id

}

tags = {

Name = "my_app"

}

}

resource "aws_route_table_association" "subnet-association" {

subnet_id = aws_subnet.my_app.id

route_table_id = aws_route_table.my_app.id

}The last resource that we’ll need to create is our internet gateway. This is the resource that actually opens up our VPC to the rest of the internet:

resource "aws_internet_gateway" "my_app" {

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

tags = {

Name = "my_app"

}

}Whew! We’re done with the network. Let’s move on to the server itself.

Creating the EC2 Instance

Start by creating a new aws_key_pair resource that we’ll include in our EC2 instance. This will give us shell access. If we need to manually connect to the server at some point in the future, we’ll use the private key on our local machine that corresponds with this credential.

resource "aws_key_pair" "ssh-key" {

key_name = "ssh-key"

public_key = var.ssh_public_key

}Next create the EC2 instance. We’re referencing many of the variables that we already set up, for the type, the size, and the availablity zone. We’re also creating it within the subnet we created earlier, and we’re passing it a security group, which we’ll create in a moment, which will control access.

resource "aws_key_pair" "ssh-key" {

key_name = "ssh-key"

public_key = var.ssh_public_key

}

resource "aws_instance" "my_app" {

ami = var.instance_ami

instance_type = var.instance_type

availability_zone = var.availability_zone

security_groups = [aws_security_group.my_app.id]

associate_public_ip_address = true

subnet_id = aws_subnet.my_app.id

key_name = "ssh-key"

### Install Docker

user_data = <<-EOF

#!/bin/bash

curl -fsSL https://get.docker.com -o get-docker.sh

sudo sh get-docker.sh

sudo groupadd docker

sudo usermod -aG docker ubuntu

newgrp docker

sudo timedatectl set-timezone America/New_York

EOF

tags = {

Name = "my_app_API"

}

}

The user_data keyword is an awesome feature that lets us pipe custom commands into the container at startup. In this case, we’re installing Docker using a bash script. The exact script could change slightly if you use a different AMI (EC2 type).

When creating an Ubuntu EC2 instance (the AMI chosen for this walkthrough) an ubuntu user will be the default user. We’re giving this user access to docker too.

Finally, I’m setting the time zone of the server to match my timezone in New York.

Creating the Security Group

The last resource we need to configure is the security group, which defines access to the specific EC2 instance.

Let’s create the security group that will open up the ports required for our application to function. First, we’ll allow SSH access on Port 22 from any IP. We could narrow this down if we only want a smaller group of computers to be able to access our resource for security reasons.

resource "aws_security_group" "my_app" {

name = "SSH + Port 3005 for API"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

ingress {

cidr_blocks = [

"0.0.0.0/0"

]

from_port = 22

to_port = 22

protocol = "tcp"

}

}Now let’s allow traffic on port 80 to reach port 80 on our machine. We do that through the use of another ingress rule

resource "aws_security_group" "my_app" {

name = "SSH + Port 3005 for API"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

ingress {

cidr_blocks = [

"0.0.0.0/0"

]

from_port = 22

to_port = 22

protocol = "tcp"

}

ingress {

cidr_blocks = [

"0.0.0.0/0"

]

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

}

}Next, we’ll allow all outgoing traffic with an egress rule.

resource "aws_security_group" "my_app" {

name = "SSH + Port 3005 for API"

vpc_id = aws_vpc.main.id

ingress {

cidr_blocks = [

"0.0.0.0/0"

]

from_port = 22

to_port = 22

protocol = "tcp"

}

ingress {

cidr_blocks = [

"0.0.0.0/0"

]

from_port = 80

to_port = 80

protocol = "tcp"

}

egress {

from_port = 0

to_port = 0

protocol = "-1"

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

}Creating the output file

For convenience (and so we don’t have to use the AWS GUI at all) we can create an output file, that’ll log out information about our network after a deploy. For simplicity’s sake, we’re only interested in the IP address of our EC2 server.

output "ec2_ip_address" {

value = aws_instance.my_app.public_ip

}

Applying our files

At this point, we should have a list of terraform files that can setup an EC2 instance with Docker. Let’s get a view of our folder.

$ ls infrastructure

ec2.tf

gateway.tf

main.tf

network.tf

security_group.tf

subnet.tf

terraform.tfvars

variables.tfWe should be able to now plan and apply our infrastucture with Terraform, using the terraform plan and terraform apply commands inside of the infrastructure folder.

$ cd infrastucture

$ terraform init

$ terraform plan

$ terraform apply --auto-approveApplying our infrastucture

Create the infrastructure by running terraform apply inside you infrastructure folder. You can also see what will be created with the terraform plan command.

Once your resources are created, you should get an output (from our output.tf file) that will show you the IP of the EC2 instance you’ve created.

We can then connect to that IP address (you may be using a different root user):

$ ssh ubuntu@your_ip_hereNote that in order to run the docker commands as the ubuntu user we’ll need our groups to be refreshed. No big deal, just lot out and log back in:

$ exit

$ ssh ubutnu@your_ip_hereNow that we’re back in the container, let’s run a simple webserver and bind it to port 80 of the machine (which is exposed to the internet):

$ docker run -dit -p 80:80 nginxdemos/helloNow when we visit your_ip_here we should see the Nginx server up and running!

Keep in mind that we may still want to configure other pieces of our webserver if this were a production application, such as SSL certificates for HTTPS and perhaps even software like fail2ban which blocks repeated SSH attempts from specific IP addresses, to make your Port 22 more secure. Alternatively, you could setup stricter routing rules for your security groups or even add a NACL for the VPC to control traffic more broadly.