Ticket 2231: just add a POST endpoint to the pricing service. Easy. PR description? Jason won’t read it anyway, so you keep it brief.

You wrap it up quickly—but then notice that the checkout service’s logging is nothing like the rest of the services. Might as well clean that up while you’re here.

You switch over all the logging… and realize the same logic is duplicated across services. Obviously, time to refactor it into a shared package. You update a few more endpoints for good measure—consistency is key, after all.

Fifteen minutes later, and most of your team is in a Zoom call, investigating an outage. The error logs, naturally, are missing the very messages you wanted to see. Turns out those logging changes broke the very logs you’d need to debug the outage…

The Virtues of Restraint

As software engineers, it’s our natural inclination to improve things. We see code that could be cleaner, more consistent, or more efficient, and we want to make it better. Most of the time, this instinct is a good thing.

But it’s easy to forget that every change, no matter how small it feels in isolation, carries risk.

Particularly in the era of AI-driven coding, engineers are being told every day to ship faster. The incentives are clear: deliver features, move tickets, keep up with the relentless pace, and you’ll be seen by management as someone who “gets stuff done” and “delivers value” for the business. Your coworker is already drowning in reviews, what’s one more 5,000-line refactor?

Practicing restraint is difficult, because it runs counter to most other pressures in the workplace. But it’s important. It means recognizing that the opportunity to improve something isn’t always the obligation to do so.

Slow is Smooth, Smooth is Fast

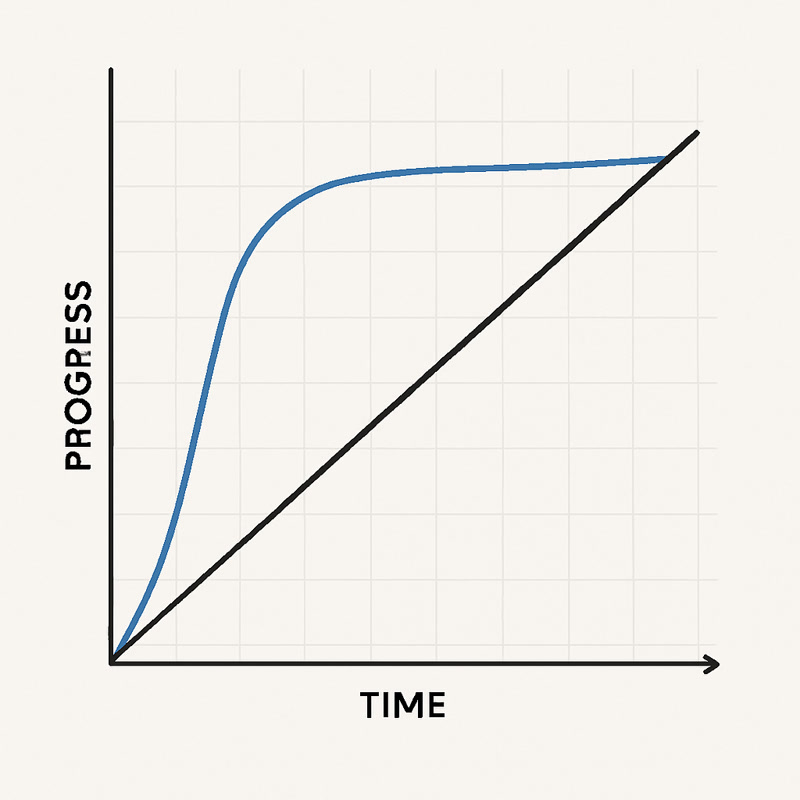

Moving more slowly is feels painful. Taking the time to review, to question your urge to refactor, and to make deliberate, well-scoped changes is counterintuitive. It feels like you’re slowing down.

But when you practice restraint, you’re not just avoiding unnecessary changes; you’re also reducing the risk of introducing bugs and instability into your codebase.

Over time, this adds up. Fewer emergencies, less cleanup. Fewer “steps backward” and remedial updates to fix something that was working previously.

Velocity on engineering teams is rarely about words per minute; it’s about building stability that lets the team accelerate without constantly having to hit the brakes. When you prioritize restraint, you’re not just slowing yourself down—you’re building a culture that permits people the time to think critically about what could go wrong.

The Case for Incrementalism

It’s not just about writing software, the same principle applies to how we approach change in our teams and processes.

When you’re tempted to overhaul a system or process, it’s easy to think that a big, sweeping change is the only way to make an impact. But often, the most effective changes come from small, incremental improvements.

Teams that move in lockstep after a series of small, visible successes tend to reach their long-term goals far more reliably than those asked to leap all at once.

John Kotter, a well-known author who focuses on organizational change, writes that transformation “is a process, not an event.” Effective change relies on building coalitions, communicating a clear vision, and celebrating short-term wins along the way.

This is true of code, it’s also true of larger process changes, like the way teams track tickets, organize sprints, or do design reviews. Dedicating time to collect input and build agreement is not just laying the groundwork for change. It is the change. Improving your processes bit by bit, and your codebase byte by byte.