You’re hard at work, developing some feature, and your colleague sends you a DM: “Can you review my pull request?”

You oblige, leave some comments, and are quickly back to your work. Five minutes later, you get another message: “Can you review the changes?”

Most developers will be familiar with this scenario. Reviewing MRs, while good for the team, is undoubtedly one of the most disruptive events that occurs during the workday. We can’t completely eliminate the context-switching that’s required for code reviews. We can bring that review process into the best editor on the planet: Neovim.

For the past couple of months, I’ve been building gitlab.nvim, a client for Neovim that lets you review and manage merge requests directly within the editor. The plugin lets you approve and revoke approval for merge requests, comment on changes, reply in discussions, and much more.

How it works

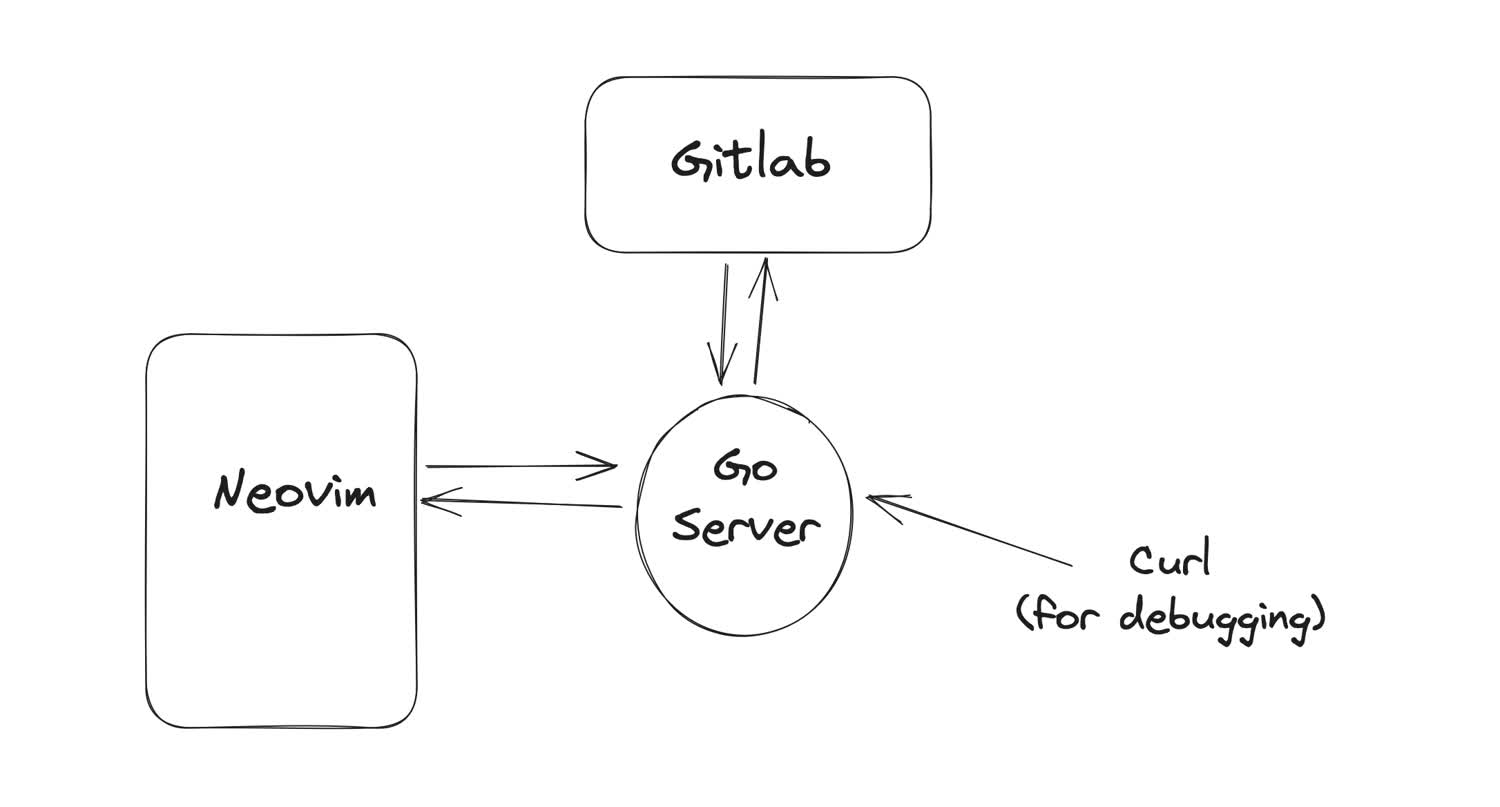

The plugin is built in Lua and Go, and is designed to interact directly with Gitlab’s APIs via the go-gitlab package — the same library that Gitlab’s CLI tool is built on.

When you start up Neovim, the plugin will initialize a Go server that runs in the background. Neovim passes JSON to that server, which sends that data over to Gitlab to update the MR that you’ve checked out in your terminal. This setup allows for the heart of the data processing to occur in Go, a type-safe and easy to debug language, while the UI code stays in the editor itself.

This separation of the Gitlab API from the plugin code also makes debugging the server separately much easier — it’s just a normal server running on your machine, and can be Curl’d like any other process.

Tracing a Request

Let’s trace a single request through the plugin: Adding an assignee to a merge request. First, you would invoke the add_reviewer() function, typically via a keybinding. The function call would look like this:

require("gitlab").add_reviewer()The plugin is written in a functional style, and this function will call a series of callbacks to ensure that the plugin state is initialized:

M.ensureState(M.ensureProjectMembers(assignees_and_reviewers.add_reviewer))The ensureState function, which is called first, is responsible for starting the Go server. If the server is already running, it calls the next callback immediately. If not, it’ll start the server first, and hit the “info” endpoint. This endpoint sets some basic state for the plugin required for other calls to function, such as the merge request’s ID, current reviewers, description and title, and so forth.

M.ensureState = function(callback)

return function()

if not M.args then

vim.notify("The gitlab.nvim state was not set. Do you have a .gitlab.nvim file configured?", vim.log.levels.ERROR)

return

end

if M.go_server_running then

callback()

return

end

-- Once the Go binary has go_server_running, call the info endpoint to set global state

M.start_server(function()

keymaps.set_keymap_keys(M.args.keymaps)

M.go_server_running = true

job.run_job("info", "GET", nil, function(data)

state.INFO = data.info

callback()

end)

end)

end

endAfter that state is initialized, the next callback — in this case ensureProjectMembers — is called. The ensureProjectMembers function is another “ensure” function that is responsible for setting state (in this case it fetches all possible members in the current project).

As an aside, this pattern of assuring state is pretty replicable and is used throughout the plugin for all the other commands. This lets us defer making API calls to Gitlab until they’re absolutely necessary:

M.summary = M.ensureState(summary.summary)

M.approve = M.ensureState(job.approve)

M.revoke = M.ensureState(job.revoke)

M.list_discussions = M.ensureState(discussions.list_discussions)

M.create_comment = M.ensureState(comment.create_comment)

M.edit_comment = M.ensureState(comment.edit_comment)

M.delete_comment = M.ensureState(comment.delete_comment)

M.toggle_resolved = M.ensureState(comment.toggle_resolved)

M.reply = M.ensureState(discussions.reply)

M.add_reviewer = M.ensureState(M.ensureProjectMembers(assignees_and_reviewers.add_reviewer))

M.delete_reviewer = M.ensureState(M.ensureProjectMembers(assignees_and_reviewers.delete_reviewer))

M.add_assignee = M.ensureState(M.ensureProjectMembers(assignees_and_reviewers.add_assignee))

M.delete_assignee = M.ensureState(M.ensureProjectMembers(assignees_and_reviewers.delete_assignee))Okay, back to the reviewer code: The add_reviewer function is called. This code is responsible for opening a popup via Neovim’s native vim.ui.select API and prompting the user to choose a reviewer from the list of available reviewers. Notice that the add_popup function is generalized to accomodate other types of popups:

M.add_reviewer = function()

M.add_popup('reviewer')

end

M.add_popup = function(type)

local plural = type .. 's'

local current = state.INFO[plural]

local eligible = M.filter_eligible(state.PROJECT_MEMBERS, current)

vim.ui.select(eligible, {

prompt = 'Choose ' .. type .. ' to add',

format_item = function(user)

return user.username .. " (" .. user.name .. ")"

end

}, function(choice)

if not choice then return end

local current_ids = u.extract(current, 'id')

table.insert(current_ids, choice.id)

local json = vim.json.encode({ ids = current_ids })

job.run_job("mr/" .. type, "PUT", json, function(data)

vim.notify(data.message, vim.log.levels.INFO)

state.INFO[plural] = data[plural]

end)

end)

endThe key line to notice here is the job.run_job line, which kicks off an API call to Go server’s /mr/reviewer endpoint. The Go server processes the results into a Lua table, which is returned to the callback function as the data variable.

What happens on the Go side of the fence?

Follow the Money

Without going too deeply into the weeds, the Go server initializes a Gitlab client and calls the appropriate API endpoint. The initialization of the Go server looks like this:

func main() {

branchName, err := getCurrentBranch()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failure: Failed to get current branch: %v", err)

}

if branchName == "main" || branchName == "master" {

log.Fatalf("Cannot run on %s branch", branchName)

}

/* Initialize Gitlab client */

var c Client

if err := c.init(branchName); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to initialize Gitlab client: %v", err)

}

m := http.NewServeMux()

m.Handle("/mr/description", withGitlabContext(http.HandlerFunc(DescriptionHandler), c))

m.Handle("/mr/reviewer", withGitlabContext(http.HandlerFunc(ReviewersHandler), c))

/* ...more handlers... */

port := fmt.Sprintf(":%s", os.Args[3])

server := &http.Server{

Addr: port,

Handler: m,

}

done := make(chan bool)

go server.ListenAndServe()

/* This print is detected by the Lua code */

fmt.Println("Server started.")

<-done

}You can see here that after the Go server is initialized, we set up a series of handlers to process JSON API calls from the Lua code. When an API call is made, we pass via Go’s context package the Gitlab client.

The handlers are responsible solely for upacking the JSON and reaching out to Gitlab. The actual handler for updating reviewers is pretty straightforward:

package main

import (

"encoding/json"

"io"

"net/http"

"github.com/xanzy/go-gitlab"

)

type ReviewerUpdateRequest struct {

Ids []int `json:"ids"`

}

type ReviewerUpdateResponse struct {

SuccessResponse

Reviewers []*gitlab.BasicUser `json:"reviewers"`

}

type ReviewersRequestResponse struct {

SuccessResponse

Reviewers []int `json:"reviewers"`

}

func ReviewersHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

c := r.Context().Value("client").(Client)

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

body, err := io.ReadAll(r.Body)

if err != nil {

c.handleError(w, err, "Could not read request body", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

defer r.Body.Close()

var reviewerUpdateRequest ReviewerUpdateRequest

err = json.Unmarshal(body, &reviewerUpdateRequest)

if err != nil {

c.handleError(w, err, "Could not read JSON from request", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

mr, res, err := c.git.MergeRequests.UpdateMergeRequest(c.projectId, c.mergeId, &gitlab.UpdateMergeRequestOptions{

ReviewerIDs: &reviewerUpdateRequest.Ids,

})

if err != nil {

c.handleError(w, err, "Could not modify merge request reviewers", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

if res.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

c.handleError(w, err, "Could not modify merge request reviewers", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

response := ReviewerUpdateResponse{

SuccessResponse: SuccessResponse{

Message: "Reviewers updated",

Status: http.StatusOK,

},

Reviewers: mr.Reviewers,

}

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(response)

}When the call is successful, that data is passed back to the Lua side of the fence, where it’s used to update the UI and notify the user that the success was successful. The UI code is responsible for updating the UI to reflect the new state of the MR. When the API call fails, the Lua job handler (not shown) will handle it and inform the user.

Compiling the Go Binary

Neovim took a quantum leap forward when maintainers embedded Lua into the editor. For the first time, developers could write plugins in a language other than Vimscript.

However, we’d be kidding ourselves if we said that Lua was the best language for API-heavy tasks, especially when robust and mature libraries already exist for external APIs, like Gitlab’s. By combining Lua and Go, we can separate the UI from the data-fetching side of the application. This makes it a lot easier to isolate bugs.

The special sauce, of course, is gluing these two sides of the fence together.

Fortunately, amazing plugin managers like Lazy have smoothed over a lot of these rough edges. In the past, this friction might have turned engineeers away from compiled solutions involving languages like Go or Rust.

Now, whenever a user updates the plugin, Lazy will re-run the compilation of the Go binary. For gitlab.nvim, that compilation step is just a Lua function, like this:

require('gitab').build()Which in turn calls the relatively straightforward build process:

M.build = function()

local command = string.format("cd %s && make", state.BIN_PATH)

local installCode = os.execute(command .. "> /dev/null")

if installCode ~= 0 then

vim.notify("Could not install gitlab.nvim!", vim.log.levels.ERROR)

return false

end

return true

endBecause the binary is being rebuilt on the host’s machine directly, there is no need to precompile the package ahead of time, which makes distribution simpler, as well as local debugging and development.

The Hard Parts

By far the most complex part of this plugin is the UI.

React, Vue, and other modern Javascript frameworks are generally declarative and reactive frameworks. They let you initialize some state and manipulate it via a series of functions. The framework then takes care of updating the UI to reflect the current state of the application.

That’s not how Neovim works. Neovim is much more procedural in nature, and as a result building UI is often clunky and redundant.

This is relieved somewhat by newer APIs that the core team is introducing. But until those APIs are more mature, building UI in Neovim will continue to be a bit of a slog, particularly when you’re dealing with nested data (like discusssion trees) where one area of the UI is branched off another. For instance, here’s the code that shows the MR summary in a popup:

M.summary = function()

descriptionPopup:mount()

local currentBuffer = vim.api.nvim_get_current_buf()

local title = state.INFO.title

local description = state.INFO.description

local lines = {}

for line in description:gmatch("[^\n]+") do

table.insert(lines, line)

table.insert(lines, "")

end

vim.schedule(function()

vim.api.nvim_buf_set_lines(currentBuffer, 0, -1, false, lines)

descriptionPopup.border:set_text("top", title, "center")

keymaps.set_popup_keymaps(descriptionPopup, M.edit_description)

end)

endThis is the simplified version of setting a popup, too, since it relies on the nui.nvim plugin for the management of the popup.

Neovim’s APIs for setting text and color are not nearly as robust as those for the web. This isn’t surprising: Neovim exists in the terminal and is bound by the laws of physics like set character widths and terminal colors. I’m excited to see how this area of the ecosystem develops in the near future.

Closing Thoughts

This plugin still has a ways to go. In particular, the line number and file detection code needs work, when it comes to leaving comments on MRs. Detecting the specific commit hash and file/line number of a comment is surprisingly difficult. Still, I’m excited to see where it goes, and I hope that it can make reviewing MRs a little less painful for Neovim users everywhere.

If you start using it or have thoughts, please feel free to drop a issue or suggestion on the project.